A paired t-test, also known as a dependent t-test or paired samples t-test, is a statistical method used to compare the means of two related groups to determine whether there is a significant difference between them. This test is particularly useful when the same subjects are measured under two different conditions or at two different points in time, making it different from an independent t-test, which compares two separate groups. The paired t-test is commonly used in experimental and observational studies where measurements are taken before and after an intervention, such as testing the effectiveness of a drug by comparing patients’ health indicators before and after treatment, or assessing the impact of a training program on employees’ performance by measuring their scores before and after training. The fundamental assumption behind this test is that the two sets of observations are not independent but instead related, making it necessary to evaluate the difference between paired observations rather than comparing the raw values themselves.

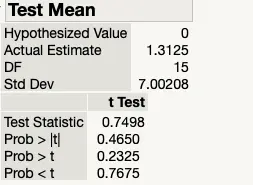

Mathematically, the paired t-test is based on computing the differences between the paired observations and analyzing whether the mean of these differences (dˉ\bar{d}dˉ) is significantly different from zero. The test statistic (ttt) is calculated using the formula:

t=dˉsd/nt = \frac{\bar{d}}{s_d / \sqrt{n}}t=sd/ndˉ

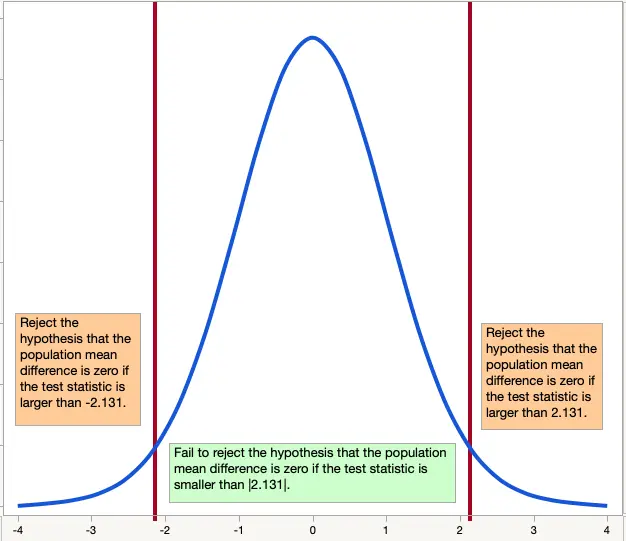

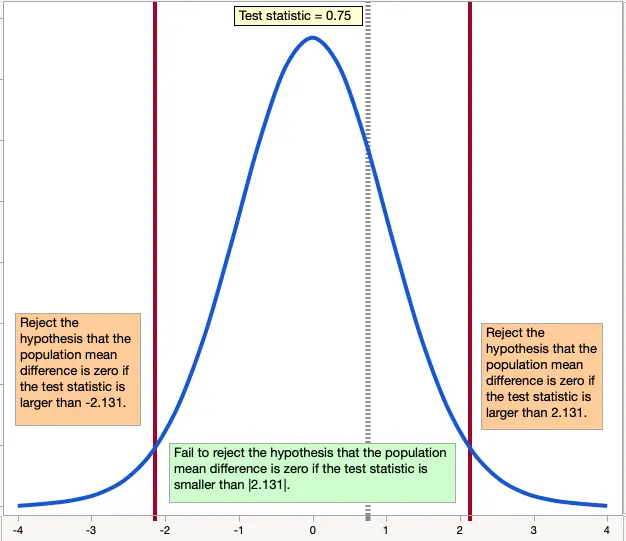

where dˉ\bar{d}dˉ represents the mean of the differences, sds_dsd is the standard deviation of these differences, and nnn is the number of pairs. The standard deviation is essential in assessing the variability of differences and ensuring the statistical robustness of the test. The null hypothesis (H0H_0H0) in a paired t-test states that there is no significant difference between the two related samples (μd=0\mu_d = 0μd=0), meaning any observed difference is likely due to random chance. The alternative hypothesis (HaH_aHa) suggests that there is a significant difference between the two sets of measurements (μd≠0\mu_d \neq 0μd=0 for a two-tailed test, or μd>0\mu_d > 0μd>0 or μd<0\mu_d < 0μd<0 for one-tailed tests).

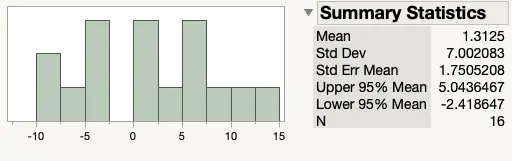

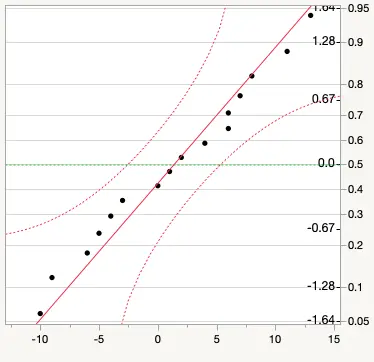

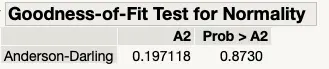

To conduct a paired t-test, the process begins with collecting paired data and computing the differences. Then, the mean and standard deviation of these differences are calculated, followed by determining the test statistic. This calculated t-value is compared with a critical value from the t-distribution table, or alternatively, a p-value is obtained. If the absolute value of the test statistic exceeds the critical value, or if the p-value is smaller than the chosen significance level (commonly 0.05), the null hypothesis is rejected, indicating that the difference between the paired samples is statistically significant. A key assumption of the paired t-test is that the differences between paired observations should be normally distributed, though this assumption can often be relaxed when the sample size is sufficiently large due to the Central Limit Theorem. Additionally, the test assumes that the data are measured on an interval or ratio scale and that observations within each pair are independent of one another.

A real-world example of a paired t-test could involve evaluating the effect of a new educational technique on student performance. Suppose a teacher administers a pre-test to a group of students before introducing a new teaching method and then gives them a post-test after implementing the method. By applying a paired t-test to analyze the difference in scores, the teacher can determine whether the new method significantly improved student learning. Similarly, in medical research, a paired t-test can assess whether a new medication reduces blood pressure by measuring patients’ blood pressure before and after taking the drug.

In summary, the paired t-test is a powerful statistical tool for analyzing differences in related groups by considering the change in measurements rather than absolute values. Its effectiveness lies in eliminating variability that might arise from differences between individuals, allowing researchers to focus solely on the impact of an intervention or treatment. However, it is crucial to check its assumptions before application, particularly the normality of differences and the independence of observations within each pair. When used correctly, the paired t-test provides meaningful insights into whether a change has occurred due to a specific factor, making it a widely used technique in fields like psychology, medicine, education, and business analytics.